Home Structural Products & Services, Stairlifts

Structural Products & Services, Stairlifts

Furniture, Clocks,

Accessories

Antiques, Folk Art,

Fine Art, Auction Houses

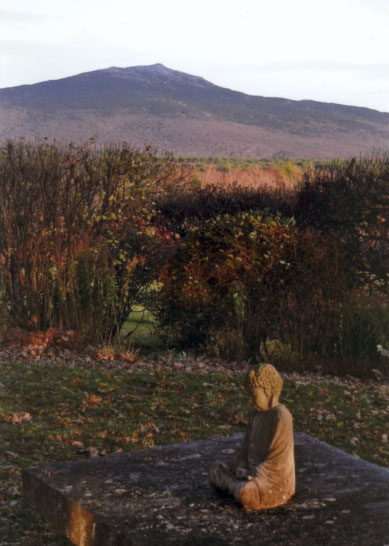

UNDER MONADNOCK

A recent headline in the Groton (Massachusetts Herald reads: “Trails Used by Emerson Bring Scouts to Monadnock Summit.” Let’s hope the Scouts follow Emerson in spirit as well as in fact—they read the essays and the poems for their own enrichment. |

|

As it turns out, the poem is twenty pages long and is an embarrassment to the popular notion of Emerson as a serene sage. Alone on the mountain, perched on a rock that’s now called Emerson’s Seat, the poet is swept up in a ferocious inner struggle. Has his aesthetic sensibility separated him irrevocably from ordinary people? He works it out, but, starting out, it is anything but serene and strikes the inner ear more like an Eric Clapton guitar solo than something by Wordsworth or even Whitman. Towards the end of the poem, the mountain speaks:

Already my rocks lie light

And soon my cone will spin.

For Emerson, everything is flow; Mount Monadnock, too, will dissolve and disappear in time. Young people, given the chance to read “Monadnoc,” would find it as intense as anything they’ve been downloading to their iPads.

Max H. Peters

Header photo by Skip Broom, HP Broom Housewright, Inc.