Home Structural Products & Services, Stairlifts

Structural Products & Services, Stairlifts

Furniture, Clocks,

Accessories

Antiques, Folk Art,

Fine Art, Auction Houses

THE VERY SPIRIT

The Americana Gospel of Rufus Porter According to Jean Lipman

By Max H. Peters

Beauty must come back to the useful arts, and the distinction between the fine and useful arts forgotten. There is no differentiation between the practical and fine arts. It seems amazing, looking back to the mid-60s, how excited some of my fellow students at Norwalk High and myself were about our artistic heroes in Europe and NewYork, while just a few miles away in Wilton Jean Lipton was sitting in her 18th century house, quietly writing books that would change the way that America looks at its art. |

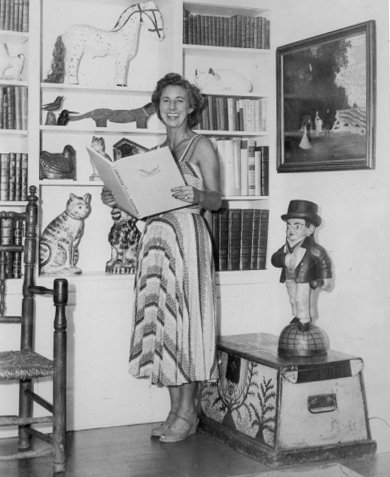

Jean Lipman stands in the living room of her Wilton, Connecticut farmhouse in 1955. Courtesy Smithsonian Institution. |

In the following paragraph from Rufus Porter Revisited,Lipton could be described as taking a similar position towards Porter as John G. Neihardt took towards Black Elk in Black Elk Speaks:

Both Jean Lipman and Rufus Porter were teaching and preaching the same truth as Emerson, who announced in “The American Scholar” in 1837 that “Our day of dependence, our long apprenticeship to the learning of other lands, draws to a close.” It’s been a longer process than Emerson might have imagined, and perhaps Jean Lipton brought it up to its final close when she wrote that Porter “suggested painting and himself painted, not only the appearance, but the very spirit of rural New England in his time.”Rufus Porter was the first American to deliberately formulate, practice andpromote the “natural” as against the academic approach to painting; the first to point to the richpossibilities of design as opposed to academic realism; the first to see the homely beauty of ruralAmerican farms and villages as unparalleled subject matter for American landscape painting. Porter was not only an art teacher but an active crusader for an honest American tradition in painting.To say that he was the first artist to appreciate and depict the plain New England countryside does not adequately define his unique position in the history of American landscape painting. Beforethe middle of the nineteenth century he wasteaching and preaching the beauties of American farm scenery, and painting it in simple, lucid scenes on the walls of hundreds of New England homes and inns, while all the famous contemporary artists were painting in the manner of the Old World masters.

The Holsaert house in Hancock, New Hampshire was decorated by Rufus Porter The Holsaert house in Hancock, New Hampshire was decorated by Rufus Porter c. 1825-1830. |