Home Structural Products & Services, Stairlifts

Structural Products & Services, Stairlifts

Furniture, Clocks,

Accessories

Antiques, Folk Art,

Fine Art, Auction Houses

FROM A CHILDHOOD IN CHINA TO A SCHOLARSHIP IN HARTFORD

by Anne M. Hamilton

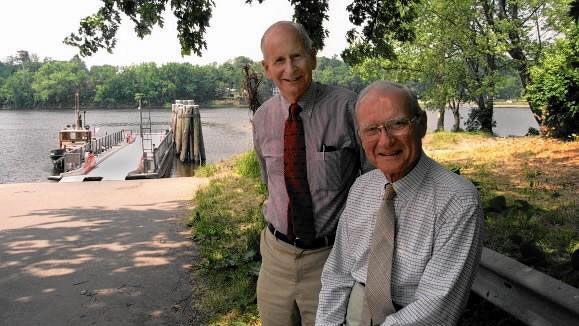

Glastonbury, Ct. - 6/8/99 - Richard Buel Jr., and J. Bard McNulty pose in front of the Glastonbury/Rocky Hill Ferry. This is one of the key locations in their book that they are co-editors on. The book is about what famous people passed through Connecticut, and is being put out by the Acorn Club. Photo by Alan Chaniewski/The Hartford Courant

Even when John Bard McNulty could no longer read, he remained a Chaucer scholar who could recite verse after verse of "The Canterbury Tales" from memory. He loved history and old houses, and wrote a history of the Hartford Courant's first 200 years. He enjoyed square dancing, especially calling out the dance steps. The common link among all these activities was language: he loved words in every shape and form. McNulty, a retired professor of English at Trinity College, died Sept. 4 at home in Glastonbury. He was 99. His childhood was unusual. His father Henry A. McNulty, an Episcopal missionary, spent most of his adult life in China, running a boarding school and presiding over church services. Bard was born on July 13,1916 in Mokanshan, China, but grew up in Suzhou, called the Venice of the East. His mother, Edith Piper McNulty, was also a missionary in China, and Bard was one of their four sons. In China, Bard was known as "Nyee-Didi," or second son, and not by his name. Among the four brothers, Bard was the mischievous child and non-conformist. Even a poor minister's pay went a long way in China in the early part of the 20th century. The McNulty house had four or five servants, and meals were opportunities for elegant dining and religious devotions. At breakfast, the children had to arrive fully dressed, hair combed and teeth brushed. First, Henry would read several Bible passages. During the porridge course, the family would discuss the meaning of the passages. Over the egg course, Henry would read the English language newspaper, and the children were expected to comment on current events. All the children's clothes, down to their underwear, were handmade and hand sewn, many of silk; transportation through the city of many lakes often was by boat; on land, it was by rickshaws or sedan chairs. Edith home-schooled all the children up to high school. The oldest son (and the two youngest boys) went to prep school in Connecticut, but Bard did not want to follow in his brother's footsteps, so he went to boarding school in Shanghai — a lot closer to home. There, he excelled in track and was elected president of his class. Bard's older brother attended Princeton, but again, Bard did not want to follow his charming, handsome brother. A friend of his father was the Episcopal bishop of Connecticut, and at the time, Trinity College was an Episcopal school, so Bard went there. He referred to himself as "China Boy"; he had never lived in the United States, and he did not know how to do laundry, make a call from a pay phone, dance the latest steps or order in a restaurant. Another student, Bill Paynter, advised him to stop talking to the waiter as though he were a servant. McNulty majored in English, and when it became time to go to graduate school, he went to New York and talked to the admissions office at Columbia. He gave them his name and said he was a direct descendant of one of the founders of Columbia College. The admissions officer contacted the college president, who replied, "Let him in, free of charge. No questions asked." After he earned his master's degree, McNulty began teaching at Trinity, and took classes at Yale University toward his Ph.D. He wrote his thesis on the poet William Wordsworth, although his true love was Geoffrey Chaucer. He received his degree in 1944. Bard's friend Paynter was working at The Courant, where McNulty joined him one day for lunch. In the elevator, McNulty introduced him to Marjorie Grant, the paper's society editor, a native of Glastonbury. They began dating and married in 1942. During World War II, he was exempt from service because he taught at Trinity in the V-12 program, designed to produce Naval officers. The McNultys lived in Glastonbury in a house they had built from plans they found in a magazine. (McNulty joked about moving to Avon, so he could be "the bard of Avon.") Over the years, Bard enlarged the original five-room ranch with several additions himself, teaching himself carpentry, tiling and roofing from books from the library. The McNulty household retained some of the formality of Bard's early years in China — without the servants, of course. Dinner was served every night on good china with sterling silver, and manners had to be impeccable. The children were expected to participate in conversations about the events of the day. "We all had a story," said Henry B. McNulty, Bard's son. "It was wonderful." After dinner, the parents went into the living room while the children did the dishes, under close quality control exerted by Bard. The family would spend the rest of the evening playing Parcheesi or Monopoly. Television, still in its earliest stages, was not allowed in the house, and when Bard finally bought one, he installed it in the garage, where the children would watch it with coats on in the winter. One of the family edicts was that no one could raise his or her voice; if there were a telephone call, the person taking it had to walk to the room where the intended recipient was located; no yelling across the rooms. Bard and Marjorie McNulty were affectionate with each other, and never left each other's company without a kiss and an "I love you." "That was very special," said Bard's son. Marjorie McNulty died in 2002. "It was an interesting house to grow up in," said Henry McNulty, who went on to become a Courant reporter, editor and the paper's first news ombudsman. Bard became hooked on square dancing, and co-founded the Glastonbury Square Dance Club. In the summers, he shared a cottage on Lake Pocotopaug in East Hampton with family members and persuaded a neighbor to let him hold a square dance in his back yard. The next summer, they held two dances, and the following year, there was a dance every week, with Bard as the caller. At Trinity, McNulty served for five years as chairman of the English department and retired as the James J. Goodwin Professor of English in 1984. He continued to teach part-time for another 15 years. He wrote 10 books mostly on his Royal manual typewriter, including "Older Than the Nation: The History of the Hartford Courant"; "Modes of Literature"; "The Correspondence of Thomas Cole and Daniel Wadsworth"; "Observed"; and "John Warner Barber's Views of Connecticut Towns." "He loved sharing knowledge with people," said Henry. "He had knowledge he wanted to share." Bard McNulty was fascinated by how people tell stories, and when he began studying the Bayeux Tapestry — an embroidered history of the Norman Conquest — he was curious about the small symbols above and below the main figures in the 230-foot long strip of linen. "He looked for some meaning in them, and discovered that the 'designs' were commentary," said Henry McNulty. Bard also read all the Perry Mason detective stories so he could study plot and character development. He also taught classes at the Glastonbury Senior Center for many years. McNulty was fluent in Chinese, although he spoke Wu, a lesser known dialect, not Mandarin. When he was older and had to count backwards from 10 for a medical test, he would recite the numbers in Chinese. He was not fond of Chinese food, except for the celebratory fried rice he would eat every Christmas Eve with his family. His experience with dirt and germs in China made him a life-long germophobe, his son said, and he would eat even a sandwich with a knife and fork. Bard McNulty is survived by his son, Henry, and daughter, Sarah Pettingell, along with three grandchildren and two great grandchildren. Copyright © 2016, Hartford Courant |

|